*Por Marcelo Gullo

The ideological vulnerability

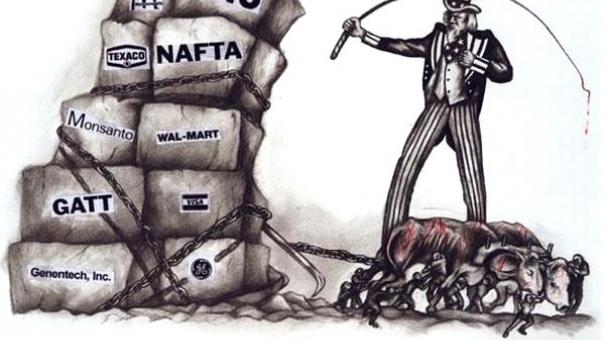

As already stated, the assumptions on which international relationships rest is given by the fact that the political units are striving to impose one to another’s will. International politics must involve a contest of wills: the will to impose or the will of not being allowed to impose the will of another. To impose its will the core states tend, in the first instance, to use soft power. The exercise of soft power, by not finding the adequate resistance from the receiving State, causes the ideological and cultural subordination that results in the subordinate State suffering from a kind of ideological immunodeficiency syndrome, whereby the receiving State loses even the will of defense. We can say, following the thought of Hans Morgenthau, that the ideal or teleological goal of soft power (in terms of Morgenthau, “cultural imperialism) is the conquest of mentalities of all citizens who make the state policy – which is wanted to be subordinated. However, for some thinkers like Juan Jose Hernandez Arregui, cultural subordination policy’s ultimate aim is not only the “conquest of mentalities” but the very destruction of the “national being” of the state subject to political subordination. Though generally, recognized Hernández Arregui, the State issuer (State metropolis in terms of Hernández Arregui) fails to annihilate the national being of the receiving State, the issuer does manage to create in the receiver “an organic ensemble of ways of thinking and feeling, a extreme world-view and finely made, that becomes in the “normal” attitude of conceptualization of reality (that is expressed as a pessimistic consideration of reality, as a general feeling of drop in value, of lack of security against its own, and the conviction that the subordination of the country and their cultural delayering is a historical predestination, with its equivalent, the ambiguous feeling of congenital ineptitude of the people who is born and the only foreign aid can redeem .

It must be noted that, although the exercise of soft power by the issuing State does not achieve total ideological subordination of the receiving State, can profoundly damage the power structure of the latter if engendered by the ideological conviction of a significant part of the population, an ideological vulnerability that results being -in times of peace- the most dangerous and serious of the potential vulnerabilities to the national power because, by conditioning the process of the formation of the worldview of an important part of citizenship and ruling elite, conditions consequently both the strategic direction of economic policy, the external policy and, what is even worse, erodes self-esteem of the population, weakening the moral and national character, the indispensable ingredients -such was taught by Morgenthau – of the national power necessary to carry out a policy to achieve the objectives of national interest. Brilliantly, Samuel Guimarães Piñeiro argues, referring to the Brazilian case, a concept that certainly is equally applicable to all countries in Latin America:

The ideological vulnerability has increased in the last twelve years by the erosion of self-esteem of the people; by he discredited the campaign of the institutions, by spreading theories about the “end of the boundaries” and charity globalization and the consequent breakdown of the concepts of nation and country; by the oppressive penetration in all mass media of the ideological product, from cinematographic films and television, up to the space given to the foreign ideologues articles in the press , and finally, the idea that there is only one output for Brazil, which is the obedience to the wishes of the “market” and the policies induced by the International Monetary Fund and their mentors, the Treasury Department and the multinational mega-banks.

In Brazil, that external ideological vulnerability is exacerbated by the rise to the positions of decision, of fundamentalist ideological neoliberal technocrats, formed mainly in American universities, imbued from the so-called “unique thinking” and its role as saviors of the country, that have imposed accounting policies, recessive and explosive debt, without fear of submission to foreign agencies. The opening to foreign capital in the media increased the possibility of external influence on the formation of the Brazilian imaginary and everyday politics itself.

In addition, the denationalized media, increases the possibility of them being used to install superfluous debates that divert the attention of the society from true essential problems. These unnecessary debates, installed in the society as central themes, act as true “distraction maneuvers”, sometimes, planned from the core of the world power. With the complicity, sometimes paid, sometimes unconscious, of professionals of the communication guided by the desire of rating as a measure of all things.

The counter-hegemonic movements

Strategies of preservation and expansion of power of hegemonic structures and subordinating States result that in each state of the periphery a specific hegemonic power structure is formed. Therefore, we qualify political movements that fought, throughout history, power structures, both locally and internationally, as a counter-hegemonic movements. These movements staged “ideological deviations” manufactured in order to escape the ideological subordination in peripheral countries, which in the peripheral countries is the first link in the chain of subordination. Throughout the twentieth century, when these movements achieved the power, whether in the only formally independent states or in colonial dependencies, these countries began to transit a process of political, economic and ideological insubordination. These movements, were fighting for industrialization or they pursued it, in any case, as a tool to “break” the subordination, as the hegemonic power structures had been allocated to these countries the role of producers of raw materials.

Historically we can state that the American Revolution was the first successful process of insubordination occurred in the periphery of the system and the independence of the Spanish American colonies the first process of failed insubordination, given that it ended up in the territorial fragmentation, the incorporation of the region to the international work division as an exporter of raw materials, and the informal subordination of Latin America to the British hegemonic power.

This led to the emergence in Latin America since the early twentieth century, of anti-hegemonic movements fighting for regional political integration to the extent that they perceived fragmentation, diagrammed and accomplished by hegemonic power structures, had reduced to the States arising from the fragmentation of their capacity for political autonomy and that, conversely, the meeting of forces come about the only logic able to regain the lost strength; Finally, politically opposed to the ruling elites in each country as they are who, unlawfully holding the local power, facilitated the designs of hegemonic centers and therefore strove for both political and social democratization, to fail, thus the organization of hegemonic structures of power locally installed.

Each of these movements had specific features that, beyond the common characteristics that equated to those arising in other States of the sub-region, distinguish them with qualities and own postulates. However, beyond their particularities, all of them were fighting for democracy, the industrialization and regional integration. All anti-hegemonic movements produced in Latin America, when they reached the government, tried to reach the threshold of power, through regional integration since they understood that it was extremely difficult to reach that goal in isolation.

Strategies of preservation and expansion of power of hegemonic structures and subordinating States result that in each state of the periphery a specific hegemonic power structure is formed. Therefore, we qualify political movements that fought, throughout history, power structures, both locally and internationally, as a counter-hegemonic movements. These movements staged “ideological deviations” manufactured in order to escape the ideological subordination in peripheral countries, which in the peripheral countries is the first link in the chain of subordination. Throughout the twentieth century, when these movements achieved the power, whether in the only formally independent states or in colonial dependencies, these countries began to transit a process of political, economic and ideological insubordination. These movements, were fighting for industrialization or they pursued it, in any case, as a tool to “break” the subordination, as the hegemonic power structures had been allocated to these countries the role of producers of raw materials.

Historically we can state that the American Revolution was the first successful process of insubordination occurred in the periphery of the system and the independence of the Spanish American colonies the first process of failed insubordination, given that it ended up in the territorial fragmentation, the incorporation of the region to the international work division as an exporter of raw materials, and the informal subordination of Latin America to the British hegemonic power.

This led to the emergence in Latin America since the early twentieth century, of anti-hegemonic movements fighting for regional political integration to the extent that they perceived fragmentation, diagrammed and accomplished by hegemonic power structures, had reduced to the States arising from the fragmentation of their capacity for political autonomy and that, conversely, the meeting of forces come about the only logic able to regain the lost strength; Finally, politically opposed to the ruling elites in each country as they are who, unlawfully holding the local power, facilitated the designs of hegemonic centers and therefore strove for both political and social democratization, to fail, thus the organization of hegemonic structures of power locally installed.

Each of these movements had specific features that, beyond the common characteristics that equated to those arising in other States of the sub-region, distinguish them with qualities and own postulates. However, beyond their particularities, all of them were fighting for democracy, the industrialization and regional integration. All anti-hegemonic movements produced in Latin America, when they reached the government, tried to reach the threshold of power, through regional integration since they understood that it was extremely difficult to reach that goal in isolation.

Seguir

Facebook

LinkedIn

Youtube